Utopian and Dystopian Dreams – An Interview with Photographer Rhiannon Adam

From moon mission candidate to disillusioned observer: photographer Rhiannon Adam reveals how space—humanity's symbol of freedom—has become a playground for billionaires. An interview about photography as truth, AI as a mirror of our biases, and the betrayal of our collective dreams

I'll start with a confession – not a particularly embarrassing one, I think. Sometimes I dream about going into space: floating in microgravity, watching a thunderstorm from above, maybe seeing the hidden face of the Moon. I'm not talking about the dreams you have while sleeping, or even dreams you want to realize someday. I'm not a scientist or an astronaut, and space tourism will probably remain too expensive for me. This dream is more like "internal fiction" – both entertainment for lazy moments and a kind of mental workout for exploring alternative realities that might help me evaluate our actual reality. It's a fragment of utopia (or dystopia) that humanity has always used to reflect on our society from another perspective. The first person to write about "utopia" – which means "no place" – was Thomas More in the sixteenth century, though Plato's Republic is also a utopia, or maybe a dystopia.

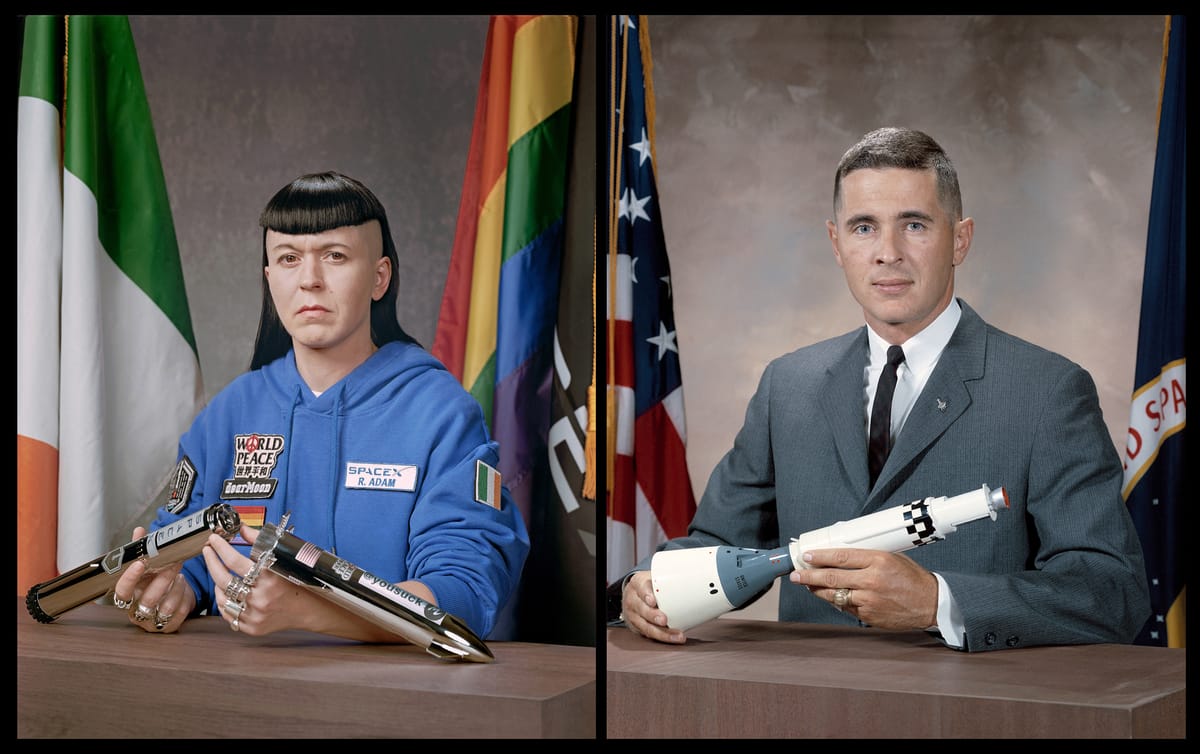

These elements – space, but mainly fiction and reality, utopia and dystopia – were at the center of a fascinating and enriching conversation I had with photographer Rhiannon Adam, who won the Verzasca Foto Festival for her project Rhi-Entry.

For Adam, going to space wasn't just a daydream. She was selected for a private space mission designed to fly around the Moon. We're talking about the dearMoon project organized by Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa. The goal was to take Maezawa and eight civilian artists on a journey meant to inspire creativity and foster global unity and peace. I'm using the past tense because the project was abruptly canceled – officially due to delays in developing the SpaceX Starship that Maezawa wanted to use. When the cancellation happened, Adam hadn't yet signed the contract – with its confidentiality and non-defamation clauses. Free to speak, she created the project Rhi-Entry.

This isn't just a personal project for coping with what I can only imagine was a crushing disappointment. As you'll see in the interview, it's a more complex discussion about space as both utopian symbol and dystopian reality – about technology, truth, photography, and what's real.

Here’s a lightly edited transcription of my conversation with Adam. The full interview is available to registered users (registration is free) – sign up to read the complete conversation.

Interview with Rhiannon Adam

This conversation is about the Moon, but I think it's better to start here on Earth. You were born in Ireland, and you spent your youth sailing with your parents around the world.

Yeah, when I was seven. My father is a boat builder, so he makes boats, and he wanted to go sailing around the world. My mother didn't want to go but my father was very persuasive. So we sold everything – our house, our car; every item we had in our house had a price tag. You could buy anything and we sold everything and we bought a boat in Ireland and it was a multicolored boat. It was crazy: different colors on each side, with big artworks on it. Everywhere we went, we were searched for drugs. Immigration would see us coming and want to search us, you know. It was a very hippie boat.

It's like, "with a boat like that, they must be hiding something".

Yeah. Well, when people have an idea of traveling on a boat, there are many different versions of this reality. Normally people are retired, have a lot of money, or they’re the third category – like sea gypsies. It's like you're an Irish traveler in a caravan but you're on a boat. Those are the three options and we were the last one. So it was from when I was seven until when I was fifteen, so eight years, and my parents divorced when I was twelve. So it was just then me and my dad alone. And you get very used to being kind of the outsider: you're not really a tourist because you don't have the money like a tourist to go and do all of the tourist things. You have your house with you, so you're a visitor, but you're not the same as them.

You get very used to being part of this outsider community and you don't really know what it's like to fit, you don't have a stable environment.

How long would you stay in different places during this eight-year journey?

Different times. You know, some places like Trinidad and Tobago, we were there for almost two years, but we would leave and come back because of visas. So we would go to Venezuela and come back and other Caribbean islands and come back. And we were in Brazil for like nine months: different places for different times. But yeah, it was a big journey from Ireland. We crossed over, we went through the Mediterranean and then to the Cape Verde Islands and crossed over to Africa. Then we crossed the Atlantic and we went to South America and then up the coast of South America. So it was a big journey and you get very used to other people's bodily functions in close proximity. It's very similar to a space capsule in a way. You become kind of at the mercy of the elements: if it's a big storm you really feel it, if it's bad weather you really understand the way the world works. Tides, storms, rain, wind, extreme heat, you're very vulnerable to these same things.

I have some sailing experience myself: nothing comparable to an eight-year trip around the world, but even on a smaller scale I know the feeling. One of the first things they said, about the life on a boat, is that you can't control the wind, but you can adjust your sails.

Yeah. So I think in a way I was very used to this idea of my own mortality. In a way you become very connected to the fact that if something disastrous happens, you know, you kind of become very aware of your own body as being this fragile thing and you are at the mercy of everything that surrounds you. And I think sometimes when you live in a city for a long time you forget these things. You forget that we are small and we are insignificant.

And you don't have many photos of this 8-year trip.

Almost none: I have very few because we didn't have a lot of money. I'm 40 and there was no digital so it was shooting on film and taking it to be developed and sometimes we would not be there long enough to collect pictures. And a lot of pictures they would get damaged also being in the humidity and the moisture and generally just being on the boat. So, it was hard to keep track of these things.

So you mostly have your personal memories.

Yeah, mainly. And sometimes you share these memories but it's strange: my mother has some but I have different ones. But when I applied for the space project, they were very interested in this trip because being in space in a way is sort of similar. You are in a life support machine and if something goes wrong, you are completely at the mercy of… you know there's no way of surviving. And you have to be okay with people in close proximity to you for a long period and you have to realize that these are the people you're stuck with. Whether you like them, you don't like them.

This is interesting because usually they say that going to space is a very different experience than being on Earth, that you see all the things in a very different way. The Earthrise photo taken during Apollo 8 mission changed the way we conceive the life on our planet and contributed to the development of environmental movements. On the Earth we can be very close to the nature and the elements, but in space we can see the world as a whole…

… in a way I think similar when you're at sea for a very long time. You lose sight of other humans for a long time, maybe for five weeks you don't see anyone apart from the people that you were with and then you're on the flat horizon and it's just blue. You're moving so slowly and then eventually you start to see a small shape like a small line and the line gets a little bigger and a little bigger and a little bigger and then eventually you start to see maybe a building and then maybe another one and your eyes adjust and then you feel yourself coming back to earth in a way and you start then to see people and life and it fills up. But for a long time you're just suspended in animation, you're just paused. And I think that part, the slow reveal of what life is, the texture of life, has a similarity, I think, with space because you're looking at it from an outsider.

And a lot of my very early pictures that I took, they were shot with a Polaroid. You know, most people when they shot with Polaroid, they shot very close up. Usually it's party pictures. But I used to always photograph landscapes on Polaroid. Very small format, but big spaces. And so it made you have to be very intimate with the picture because the picture is small: if you want to see it, you have to wait your turn. And I used to photograph these intimate landscapes but they were tiny, tiny little people always in big spaces. And it was kind of because when I was a kid, I would look with binoculars to try and see people on the shore, just to remind myself that other kids, other lives, other people existed because you feel like you're in a bubble, like you can't connect really with that as being real life because your reality is this capsule. And so when I look at my very early pictures, I'm like, "Wow, it's like I'm looking at the world through glass, like I'm not really part of it and I can't connect".

So the choice of Polaroid was for this research of strong connection with the reality?

Because it was the small intimate thing. But also when I was a kid, instead of taking pictures – as I say, I have almost no pictures – I would take physical thing. Like maybe you had a beer and you put your beer down and it leaves a mark on a piece of paper and I would write your name and I would write the date and I would keep the piece of paper because this would be the memory of our conversation.

And a Polaroid in a way is also completely down to the elements. There is a purity in the way that the chemistry inside of the package reacts in the moment that we are in. If we are in this room, it has certain humidity, a certain temperature. If I hold it too tight, it will have marks on it. It will bear the marks of its birth, of its becoming in a way that other photography doesn't happen. You know, if you take a digital picture, you can go later on your computer and you can change it, but you can never touch it. If I develop with film, I go into a dark room and I can change the temperature of the bath and it will change what color the film will be.

I can change things about it. I can dodge, I can burn, I can change elements in the dark room. But the Polaroid is the physical manifestation of the picture in its purest form. You cannot edit it, you cannot crop it, you cannot change its color. It reacts chemically to the environment that it is in and it reacts chemically to my body. If I put it in my pocket and I warm it, it is a reaction. It is a collaboration with my physical body. And so there was something very pure about the Polaroid form which is very different than even wet plate collodion or an old process like tintype. With those, I have control when I apply the coating. But with Polaroid everything else is added. It's the environment that is changing it. So, it's a co-authorship between me as the photographer and the environment the picture is taken in.

So, the value of traditional – chemical, analog, whatever we want to call it – photography is in this physical connection with the reality? There is a continuity that digital photography is breaking up?

Yeah. It's like a translation. If you read the original you understand the true intention of the author, if you read the translated version and you know the original language you go "yeah it means this but it kind of doesn't". It's always like a parallel. And I think...

I have many friends who are translators and I'm not sure they will fully agree with you, but perhaps to a certain point they do because they know the difficulties.

Yeah the difficulty of translation. And I think that with digital photography, what often happens is that you try to transform the image into the version you had in your mind, not the version that was really there. It becomes a kind of wishful thinking: a digital picture sometimes creates this imagined reality—something not quite aligned with what I see with my eyes. But sometimes I want to see the flaw, to see that something is not perfect. I don’t want perfection all the time. Polaroid, in this way, embraces imperfection.

When I was applying for this dearMoon project, I had to go through many rounds. There were many interviews, online interviews with so many different candidates applying and we would be put in – remember it was during the pandemic – with breakout rooms and then you would be having these conversations with different people and talking about all kinds of things: life perspective, what you would do in a crisis, all these different things. Then when it got to the stages of really applying with what work we were doing, I also said that in the age of AI we are distrusting the image with retouching. Even with the first moon landings, we distrusted that it ever happened. We have so many conspiracy theories, about the moon landings.

Yeah, they analyze the pictures of Apollo Mission in search for any supposed flaw…

Yeah: you can zoom in here and this doesn't look consistent and oh the flag, it's flying and there's no wind on the moon… all of these things. All of them have an explanation but there is something very interesting about that line between fact and fiction and what we can trust and the photograph as being seen as evidence or not.

Edwin Land, who made Polaroid, created the square version with the packet of chemicals which we call "integral film" where everything is contained and not the peel-apart kind where you throw half away. But integral film was invented in 1972 and 1972 was the last Apollo mission. So the two never coincided for going to the Moon.

And more about Edwin Land – because, you know, a lot of his fortune early on actually came through the military and surveillance. He even wrote a chapter for President Eisenhower on the space program, called “To the Moon and the Moon as a Goal”. So he’s writing this chapter, and then this new product comes out, and suddenly it’s on the cover of Life magazine as “The Man and His Magic Camera”. It was groundbreaking for so many reasons. Today we think of Polaroid as something “cute,” “quaint", but back then it was used in police departments—because you couldn’t fake it. It was used in insurance cases: if there was an arson, you could take photos on the spot and they couldn’t be altered. Every single picture had a unique number. It carried a record, a trace of where it came from. You could read the number and know: this was the factory, this was the machine, this was the operator, this was the date. Every photo had its own unique identity.

But you are an artistic photographer. So why are you so interested in the evidentiary value of pictures? Digital photography and AI generated images aren't better suitably for artistic freedom?

I suppose you know photography has never really been true. I mean as long as we've had photography we have selected, we have cropped, we have changed things. Photography is a complicated term because you say you're a photographer, the first question normally you receive is "weddings or babies?" So there are as many different types of photographers as there are musicians, right?

And I have played with AI. I have used it in a project. But I've used it in a way where it's like questioning history. How do we trust records? I think record-keeping is important, up to a point. But even with a Polaroid—yes, it’s anchored in reality—but it’s still filtered through the lens of that specific technology, the way it sees the world. And if you know how to read it, you can find all kinds of evidence inside a picture.

I can tell if it was a cold day or a warm day. It might have been taken before I was even born, and yet I can still read it. It’s like an archaeological dig: when you find a piece of pottery, you can say, from these lines, from these marks, I can tell a lot about the world it came from. A Polaroid works in a similar way.

You spoke about a project involving AI. Can you tell more?

I'm interested in the way that AI becomes the everyman. It becomes a collection of all of our collective biases and thoughts. It becomes the level playing field – the average of human imagination. It's not necessarily the best of human imagination; It's the average because it's taking inspiration from everything. It doesn't have a hierarchical choice. It doesn't say this thing is better than this thing because it's not choosing quality. It's choosing quantity and using it based purely on information. So I think it's very interesting to see AI as the common denominator between all of us. If we want to find out, okay, what does the world really think about this image of war? And you ask it and what it comes back with will be an average of all of the people who've been positively looking at it, all of the people negatively. This will be the average. And I think there's something interesting in finding what humanity's average is.

And when I was working with AI in the previous project, I used it in this way: I put in different prompts, and one of them was imagining queer history if certain laws had been different. Henry VIII exported, through colonialism, the anti-buggery law to Africa: that law was carried into the colonies, and these colonies have still kept that law from Henry VIII's time. This is why people in Uganda can have the death penalty for being gay: it's not because of Uganda, it's because of Henry VIII.

A colonial heritage.

Yeah, and how these things trickle down and we say, "Ah, Africa, it's terrible what they do to gay people". But actually, no, it's the UK. It was a king a long time ago who had many wives and used to kill them if he didn't like them anymore or wanted to have a new one. This same guy is the reason why gay people can have the death penalty in Uganda. So I used AI to imagine actually if Henry VIII had a gay lover, if Margaret Thatcher had gone to a gay pride march in 1988 instead of introducing a law banning education about homosexuality in schools. I was making these images and I was trying to imagine if these things had happened. Maybe if homosexuality hadn't been so outlawed we would have not just thought AIDS was a gay disease and millions of people would not have died.

There's this real impact between these things because you know, you label something as "okay we don't care about these people, they're criminals", then we don't care about their healthcare. But then you forget actually it's not just isolated to the small group of people you don't like. So I was making this project that was trying to imagine if the AIDS crisis had not happened what would a happy old people's home of older gay men look like? Or what would queer happiness look like if there hadn't have been this generational trauma carried?

And the results?

When I was searching to make these images, what was horrifying is that I was asking, okay, "older gay happy couple in their 70s walking along a beach," they would come out looking monstrous. If I put the same prompt and I said "a heterosexual couple walking along the beach," they came out looking like normal humans. And if I said "a homosexual couple kissing at a family picnic, they are age 75 and 80," they would come out looking like monsters and everyone else in the picnic was normal. And it was like this chilling part because AI is generating this world, where it's just creating from what it's being fed. You know, we are searching for these things. It scrapes the internet for information. If the people on the internet are saying "okay, this is bad, this is horrible, this is monstrous, this is wrong" the image that is created is horrible, it's monstrous, it's wrong. So, it's just a mirror. AI is a mirror.

A mirror but also a magnifier that show us things that we don't see.

And it shows sometimes the darkness in ourselves. And I think this part is maybe the most interesting about AI, more than what it can imagine creatively because creatively right now it's very limited to borrowing aesthetics from here, from there, from this and that. And as an artist you feel conflicted also because, you know, AI is learning from all of us…

I can say to it I would like to create a David Bailey style portrait of, I don't know, pick an actor and it will make me something. But I didn't take it. It's not mine. It's borrowing an aesthetic from someone else. And so as an artist yeah you can control certain parts but you can't really control the AI aesthetic 100%. You know it's... part of it will always decide what it wants to do and you can change it and you say "in the style of" but you always have to give it a style reference. It's always "in the style of Manet, in the style of…". It's not really generating something that's new and fresh, it's generating from what has become. And as an artist you're always trying to create something that is looking forwards not always just to look back. And even though with my work I work a lot with history and archive material, I try to situate the work in a bigger context.

Rhi-Entry, for example, it's about my experience, it's about space but actually it's about our relationship with looking up. It's about our relationship with the stars. 117 billion humans have lived on this earth and we have all looked at the same sky. And then suddenly we are launching satellites: we have changed that sky in fifty years. 117 billion humans in the history of the earth have looked at that same sky with no changes and now in 50 years we are changing it. What does that mean for our future? What does that mean for our collective identity when we are no longer looking at the same continuity? When we look at the sky, we are looking at deep time. We are looking at history, we're looking at everything that has ever been, everything that ever was. This is our history: we changed so much on Earth, but from out there, we look the same as we always did. You know, there's a leveling of looking at the earth from far away. We don't look like this corrupt planet where we are fighting wars, we are destroying the environment. We look the same like we always did. It puts a lot of things into kind of some form of perspective.

Yeah. I think it's time to talk about the project you are here for, Rhi-Entry, that comes as a reaction to the bad news that the dearMoon mission was cancelled. So… I can only imagine the disillusion. How do you respond to that?

I'm always interested in this line between what is real and what is not real. Like we've spoken about, this line between fiction and reality or utopia and dystopia. It's the same thing, utopia and dystopia. It's one half of the same coin.

And I guess in your own life you never really know when one thing is about to change. You never know when you know you are walking down the road one day and everything is completely fine and then you get hit by a car or a big tragedy happens to someone in your family or you find out you have cancer.

And this, the dearMoon cancellation, was a really big rug pull because it's not that I had waited my whole life to go to space. It was not a reality for me: statistically as a woman the chances of ever going to space is infinitesimally small. Only twenty-four people have ever been around the moon. All of them have been American men. Every single one. Yeah. We have the European Space Program sends like a couple of people: It's not a big program and I'm not a scientist. I am not a multi-billionaire, I'm not friends with Richard Branson or Jeff Bezos…

Or his then fiancé now wife…

Yeah. I'm a gay woman and historically that has also been a very excluded part. Homosexuality in space? The line to go to space was always through the military, and that blocked the way. Even now, with Trump in America saying “no DEI,” if you’re gay in the military you can still be discharged. And that’s the line you have to follow to become an astronaut.

So statistically my chances of going to space were so small that I never even dared to think about it. It always felt like something other people would do, not me.

And in a way, I wanted my story to say that maybe space really is for everyone. Symbolically, space has always held that meaning—especially for queer people—because out there there’s no legislation telling you whether you can exist or not, no one saying your life is right or wrong. Out there it’s supposed to mean freedom.

But like I say about utopia and dystopia, the symbolism is that it's this utopian idea with no borders. But the reality is that very few people are controlling it. That access is very tightly controlled, that you're already excluded before you start. And to be out there, you have to be in a life support machine. You have to be kind of connected to a government perhaps that you don't agree with. It's ultimate freedom, but it's ultimate entrapment. It's these two lines and I was very interested in that and what that means historically.

And so when I was selected for the project, you know, of course it was like unbelievable. I could never have imagined from one million people to eight and then I'm the only woman on the confirmed crew. Statistically, it's crazy. And in some ways, it takes over before you even go. It takes over your every waking thought. It changes how you see everything: a leaf, the ground, the sky, the stars, the people in your life. You start reckoning with your own mortality, because statistically there’s also a high chance that something could go wrong. You have to prepare everyone in your life for the fact that you’re willing to die for this.

It’s very real – almost like going to war, where you prepare knowing this may be the end, but you still believe in the cause. You start to understand your place in that history, in that legacy of spaceflight – this story of utopia and dystopia, of freedom and entrapment, of a perspective on Earth that is larger than yourself. And you reach a point where you say "Yes, I could actually die". And you have to make peace with that idea.

A change in perspective.

Yeah. It is a bit like being given a diagnosis of something and maybe it goes well, maybe it doesn't, but you think a lot about how to make something feel meaningful. And so, it's a very hard loss because it's not just the loss of the trip. It’s also the loss of a version of yourself – the version that could once be blissfully ignorant about certain things.

And then when you start to connect with the idea of space flight, you also start to connect with the dark side of it. You start to connect with, okay, the satellites that we are putting out, the power that we have put in these people's hands. You start to be in rooms with very important people making decisions and you start to see them for what they are. You start to see them for these flawed human beings that have the possibility to change the course of the entire of human history in a room like we are in now. And they're just talking about it casually like it doesn't matter. You start to see how big business influences politics and we have just seen it. You know, Elon Musk gave so much money to the Trump campaign. Trump ends up being elected. Maybe if Elon Musk had not intervened in the election, we wouldn't be where we are. And why did Elon Musk did that? Well, he wanted to reach Mars and Donald Trump promised he would cut red tape. He would let the Federal Aviation Administration allow Elon Musk to launch more rockets to get to his goals faster. So, of course, you're going to back the guy that can help your business.

So, you think of space as being this freedom, this poetic thing. We have Debussy composing music about it, poets writing sonnets… but the reality is that it is a military controlled zone. We are a small target from out there. We are at the mercy of billionaires who can change the entire course of human history and we should be more afraid. But fiction has influenced our experience of space so much: the hero films, the astronaut walk-outs – where it's like the perfect specimen of humanity is these astronauts. We look at them as these perfect versions of humanity and they are also like with AI, like the average. We take these people and we take away every flaw and what we are left with is this like magnolia-paint version of a human and this is an astronaut. We think of them as heroes, but they are basically military workers paid by governments.

So was the cancellation like utopia destroyed by dystopia – by reality?

In a way, I think our trip could have been that opportunity – to inspire ordinary people to care about space, to engage more with why we should worry about the future. Why it's not just this abstract concept? Why actually this matters? We should be protesting on the streets about what happens in space with the same care that we protest about climate change or about war. We should care about space in the same way.

Now we are in the second space race. We have a chance to have an influence of what happens out there. But because we think "ah it's not for us, it's someone else's," we can't connect to it in a real way because it's only hero astronauts or it's billionaires. And it's far and we don't really understand it. But actually what happens there really affects what happens to every single human on this earth. This is our ecosystem as much as the earth is our ecosystem and we don't care about it.

And I was hoping that our mission was actually a link point to... in the same way that [the astronaut from Apollo 8] Bill Anders said when they took Earthrise: they should have sent poets because we couldn’t understand the grandeur of what we experienced. And then in all this time they have never sent poets. They have never sent artists. They have never sent writers. They have never sent anyone who can be the translator of this experience out there to this experience here. We have never had the translator. We have people who are bought and paid for. We have government workers who have to say something that supports their government. We've never had people that can speak freely. And this dearMoon project, it was the line when that could have happened.

And then of course when it was cancelled, it also coincided with all of this political craziness in the United States. And Elon Musk – we were meant to travel on his rocket – suddenly becomes the world’s arch-nemesis. He becomes this Dr. Evil figure. It was a symbolic ending of this collective dream where from the dawn of time, from cave paintings, humans have looked at these stars and we have dreamed about going there or wondered what it is. And this could have been the moment when we finally sent the poets, the translators—the people who could explain why we should care. Not so much about what happens there, but about what happens here because of it. Why caring about space is really about caring for ourselves.

So the project Rhi-Entry is this "return to reality", the realization that we don't live in a utopia.

Yeah. And, you know, we’re always just one decision away, one line away from everything changing.

The project Rhi-Entry has also a lot of applications from the past, from the 50s when people were applying to go to space even before we had even sent someone to go to space. There are all these people applying to go to space from these early exhibitions and the reasons people wanted to go to space is the same reasons that we are struggling now. There are letters and they say "I want to leave this world of war. I cannot find a place of my own. This world is too crowded". The people in the 50s were writing the same thing as what we are writing now. And from space we don't see war but it is becoming a place where we will fight wars.

We have an opportunity now to actually stand up for ourselves and say that this is not what we want. We have a gentleman's agreement: the Outer Space Treaty. It's a handshake. "Sure, we're not going to bomb you from out there." But we see agreements with NATO, they get broken. We see agreements all over the world about ceasefires, they get broken. What’s to say this gentleman’s agreement won’t change one day? You know when you look at the nations that are out there in space for the most part it's China, it's Russia, it's the United States. Europe has a small part, Japan a small part, India a small part but mostly it's Russia, the United States and China. They are the ones controlling space and it's a gentleman's agreement that they will not cause a war.

And so this project is about why we should care, but it's connecting with the history of space flight. This idea of the hero, why we need to move away from this idea of the hero and reimagine what that is, because that hero idea is not serving us. Because the idea of the hero is excluding you and me from seeing ourselves as having any relevance in this story. Rhi-Entry it's my own psychological recalibration into normal life. But I can never unsee what I saw, I can't unhear what I heard in those rooms, what I saw with my eyes. I can't change it and I can't ever rewind the clock.you think you have autonomy, and then one day a billionaire decides that they're going to change everything. One day the billionaire chooses that we go to space; the next day, that we don’t. In the end, we are all at the mercy of these billionaires making these decisions about our future. And mine is just the apex where you can really see it happening, but it's happening to all of us in different ways. Mine just happens to be very clear where I became a billionaire's toy.

I spoke to him when it was being cancelled. We talked about our realities. The project originally was meant to inspire world peace. That was the mission of dearMoon – we were meant to make artwork that was in some way to inspire world peace. Now I don't make campaigning work but I make work that touches on, I imagine if certain things had not happened or I make work about a remote island community where abuse became commonplace. I talk a lot about government interventions. I make work that connects to physical earth and our contamination of it. So my projects are not about world peace but they are providing in some way a conversation starter where we consider our role as authors in our own destiny and we have choices. We have a voice. We can use it. So all of my work in some way it's connected to these ideas of common shared humanity and where we've gone wrong and where we can learn from our past mistakes and not make them again.

Also learning to imagine an alternative.

An alternative, yeah. And so this was the idea of dearMoon. We make this work, but actually the billionaire cancels the project. I presented ideas to him. I said, "Okay, I understand if you want to cancel this project, we are in the middle of the Gaza war, we are in the middle of a war with Ukraine, we are in the middle of so many wars around the world, smaller, bigger, more publicized wars, more well-known wars. We are in a world that is ripping itself apart. I can understand if you want to cancel this project and you want to divert the money that you were going to spend on this project and you wanted to spend it on something good. You want to spend it on aid. You want to spend it on solutions to help people. You want to start a platform for world leaders to come together to discuss in an informal way. You want to… there were many things you could have done – world leaders’ summer camp. You are that influential with that much money you could have done what you wanted". But he doesn't. He does nothing.

This is the part that I found very hard to deal with. He uses this emblem of world peace. He floated his company on the stock market with "world peace, world peace" banners and then when it comes to it, when he drops the project, he doesn't take the money and do something good. He doesn't help anyone. He doesn't make an artist fellowship on Earth to deal with projects that are changing perspectives to encourage world peace. He doesn't do any of these things. He starts a race-car team.

And this, I think, is actually in some ways the reality we are all living in. A narrative will suit someone until it doesn't suit them anymore and then they're willing to throw it all away. And this was the part that I found the hardest. It wasn't even so much for me the loss of the project. It was the disillusionment to think that there was one of those guys who has so much power and influence who could have done something good, who decided to do nothing good when there was a glimmer of hope that maybe we were not all doomed. And that part is the part that I found the hardest to deal with because that is real for all of us that we are just here being customers for Jeff Bezos. We are here just for that.

We started speaking of being at the mercy of the elements… and the billionaires are the new elements.

We are speaking of being at the mercy of powerful people. Power, riches, greed – we are at the mercy of the worst sides that AI shows us, the darkest parts of humanity. These are the parts that we are becoming slaves to, in a way, these darkest parts of humanity which is cruelty, it's selfishness, it's those parts and that is what we are not even realizing. You know everything on this earth is there to be exploited for profit.

And this is what Rhi-Entry is really about. It's like wow, we have lost this collective dream for something so cheap and so... it may be this dream that was unattainable to so many people but if we were to be the bridge where suddenly real people are like "I know that person, she reminds me of someone I know" or "she looks a bit like me" or "she talks like me" or "she's average like me". It makes this thing accessible and it makes us feel we have some power. And this is where we have lost is that we collectively as humans we've forgotten that we have any power because all we see is this influence or we are the slaves of social media that is controlling the way that we experience the world which are owned by those same people that want to exploit us for sales. So this project is about my experience but it's about my experience as a parallel for all of us.

So… none of us was selected for a space mission, but I think the disillusionment is shared. We all carry that same hope: that somehow things might turn out better.

Optimism is a very human trait, right?

Yes, but we need also to deal with the reality.

And this is why, like I still care. We are often in denial of reality. We need to deal with what is here, not what we can imagine. And in the last 50 years, we have turned technologists into gods. We have turned technologists into gods where we have such a belief that technology can save us that we can make a problem and then we believe technology will always find a way of fixing it. So, we don't believe that the problem matters. We're like, "Okay, yeah, yeah, yeah. We see there is an issue here, but don't worry, we'll invent something to fix it". And this is what we do. We are constantly putting a plaster on a problem.

Instead of looking at the problem…

It’s like patching things all the time. Like, “ah,” but then a government comes in and changes direction. Donald Trump, for example, saying, “Climate change? What is that?”. One person with that much power – backed by money raised by someone who wants to launch rockets – can suddenly decide what happens to our climate. He can cut climate funding. He can cut cancer research. He can cut support for AIDS and HIV. And people die because someone wants to send rockets to space.

We tend to think these are separate issues, but they’re not. We live in a single, closed ecosystem. Like water: the amount of water we have is all we will ever have. And so this project speaks to that – maybe in a small way now, but it will grow, change, expand. Still, the reality is: what we see now is just the tip of the iceberg.