Beyond True and False: How AI Rewrites the Language Games of Images

Are AI-generated images false? To answer, we must understand what makes any image true. Images play various roles in different language games—and AI is wiping the slate clean of the codes we used to read them.

Here we are: another newsletter about images—after the interview with the photographer Rhiannon Adam and a piece on how news photos depict heat waves.

It’s odd, for me, to have this interest in images: I express my thoughts in words, not pictures. Of course I take photos, as everyone does, but mainly for "personal use" (happy memories in the form of mediocre images stored on my phone) and my drawing skills are rather poor. Still, I'm interested in how public knowledge is made, and images are a core part of it. So, I think it is important to understand the place of pictures in our shared knowledge, what role they can play in the great game of public discourse. And whether AI-generated images can serve the same role, work differently, or completely overturn the existing rules.

The cornerstone of this topic is that AI-generated images are at least changing the level of the game. A terrific, and perhaps terrifying, example is the AI propaganda used in particular by far-right movements. President Trump has posted AI-generated content dozens of times on his Truth Social account: Stuart A. Thompson has analyzed this AI bonanza: cosplaying as the pope in one fake image, watching agents arrest Barack Obama in another, standing atop a mountain having "conquered" Canada in a third (observing a mountain that strikingly recalls the iconic Matterhorn, a peak that has nothing to do with Canada or America). Political experts note that even the most anodyne uses of AI by the president normalize these tools as a new type of political propaganda. "It's designed to go viral, it's clearly fake, it's got this absurdist kind of tone to it", says Henry Ajder, who runs an AI consultancy. "But there's often still some kind of messaging in there". It redefines – or in some cases discards – the idea of being "presidential".

But in this newsletter I’m interested in a more general reasoning: trying to understand if, and why, AI-generated images—or “images generated using AI”, because AI is an instrument in the hand of a human being that has decided to make or share them—are false and what count as a “true” image.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Image Truth

So, the starting point is the truth of images. But facing this question is like opening two Pandora's boxes full of philosophical troubles.

The first box concerns the concept of truth itself: what makes some of the things we say or think true and others not? Long story short, you'll find theories of correspondence (a statement is true if it corresponds to reality or facts), epistemic theories (which study how we obtain or justify statements we consider true) or deflationist ones (according to which truth isn't a real property of propositions, but just a linguistic way to emphasize what we're asserting). Very important, and interesting, are also all the analyses on lying and how it's possible to deceive even by saying something true.

The second Pandora’s box concerns images: even ignoring the question of the nature of these objects—and also setting aside the complicated status of mental images that a significant part of the population can't even form—there remains the question of whether images can be bearers of truth. In other words: are images one of those "things" that can legitimately be true or false? Ernst Gombrich, the great art historian, was certainly right when he said that images aren't propositions and therefore can't be true or false, just as a statement can't be blue or green (he wrote that in an essay contained in Art and Illusion). Traditionally, being true or false concerns declarative (apophantic) statements and their propositions, excluding linguistic expressions like commands or questions; it would be strange to include images instead.

However, we commonly speak of true images and false images and it's important to understand why (and whether it's a legitimate use or one of the many "imperfections" of our natural language).

Two Ideas of Image Truth

When we say an image is true (or false), we're referring roughly to two concepts, or rather two groups of distinct concepts.

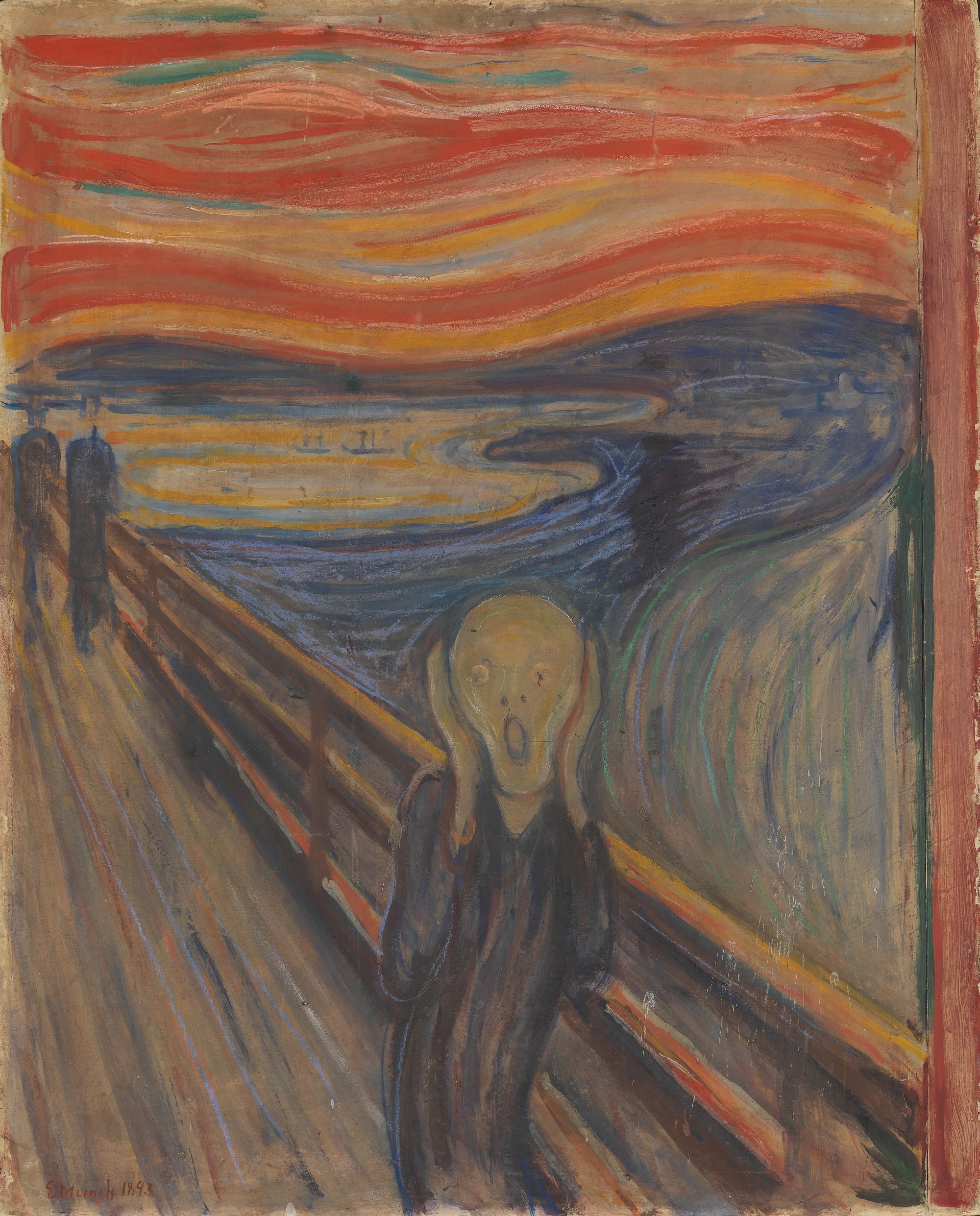

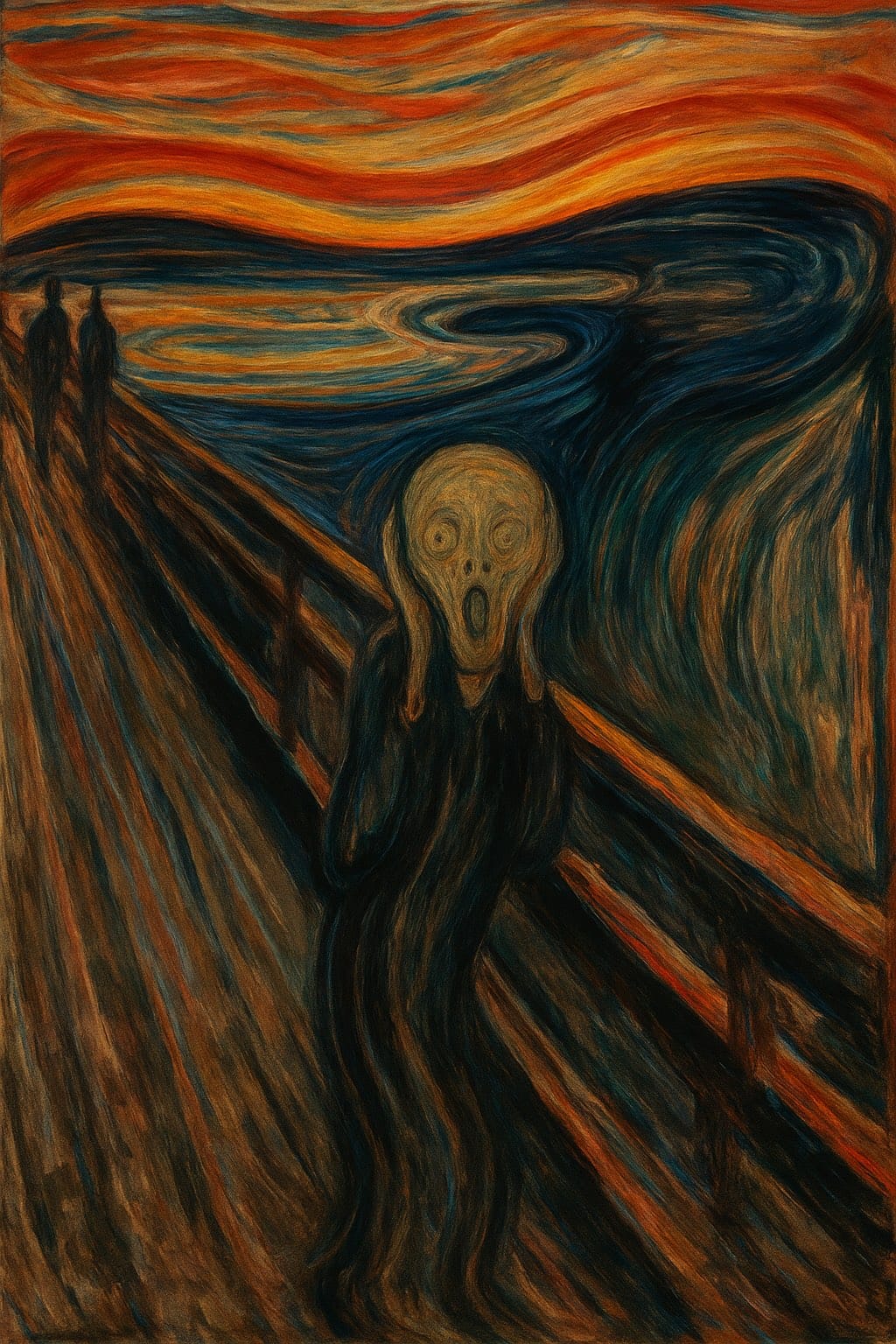

The first, which we might define as "truth as authenticity", refers to the characteristics of the image as an object. "It's the real Scream by Edvard Munch" in the sense that it's one of the works with this title made directly by the Norwegian artist and not by a forger. But at the same time, we can consider a reproduction of that work faithful to the original as true, contrasting it with a reinterpretation, a parody or a version of the work created using generative AI starting from a description of the painting. Drawings and paintings made from life are also true, in the sense of authentic, and obviously non-manipulated photographs.

The original Scream, and on the right, the version recreated by ChatGPT from a description of the painting.

However, these last two cases bring us to the second way in which an image can be true or false and which no longer concerns the image as an object but the image as a representation of something and especially as an expression of a proposition; for this reason I'll refer to this second meaning as "propositional truth". An illustration can be true because it's made, as mentioned, "from life", but also because it correctly reproduces the salient characteristics of what's depicted, ranging from the extreme realism of the first anatomical illustrations to the essential lines in subway maps, whose truth depends simply on the succession of stops and interchanges.

A photograph can be true, in the sense of authentic, because it hasn't been significantly modified, but at the same time it can be false (in a propositional sense) because it's the result of staging and therefore doesn't show the real unfolding of events. Context matters, obviously: no one would consider a wedding photo false because the couple posed; conversely, in major naturalistic photography competitions, it's forbidden to use any practice that, like bait or calls, could modify the natural behavior of animals.

However, even an unmodified photograph depicting an unmanipulated scene can be false, in a propositional sense, if the photo expresses an untrue proposition. This is the case with an incorrect or imprecise caption, but also with an image that represents marginal aspects as central: think of the photograph of a few violent demonstrators within a peaceful march, as well as many advertising images that suggest unrealistic characteristics. For these latter cases, one could say—and this is indeed Gombrich's position, in some ways similar to deflationist theories of truth—that what's true or false is not so much the image but the statement that accompanies it: an elegant solution that would free image analysis from having to deal with the theme of propositional truth, limiting itself, possibly, to authenticity (which in this framework wouldn't need to be called "truth").

But I find this position unsatisfactory for two reasons. The first is that the theme of an image's authenticity, to be understood in its entirety, must be framed within a more general reflection that also includes propositional truth, which is impossible if we neatly separate the two domains. The second reason is that it's not always possible to identify a precise statement that gives verbal form to the proposition represented by an image: this is the case not only for many advertising images, but also for prejudices conveyed by stereotypical images.

It's important to note that, although conceptually distinct, the two forms of image truth are often interconnected in complex ways. An image's truth as authenticity often guarantees its propositional truth: we presume that an unmanipulated photograph faithfully represents what the photographer saw, that an anatomical drawing made "from life" during a dissection conveys accurate information about the structure of the human body, that a scientific image created from collected data gives us true information about the phenomenon studied, and so on.

Beyond Image Truth

Before continuing, we must consider that the question of image truth concerns only a part—and not even the largest part—of our relationship with images.

In a well-known passage of the Philosophical Investigations, Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote that words are like the tools in a toolbox. There's a hammer, pliers, a saw, a screwdriver, a ruler, a glue pot, glue, nails and screws: we use these tools in very different ways and it would be naive to ignore these differences just because they're all tools in a toolbox. The function of each tool determines how we use it and how we judge whether it's doing its job well.

The same goes for images. A selfie serves a completely different purpose than a profile portrait on an institutional website, even though both are photographs of faces. An abstract painting may superficially resemble a subway map or the output of a sensor used in a scientific experiment—all three might consist of colored lines on a surface—but their functions are radically different, and so are the criteria we use to evaluate them.

Still using Wittgensteinian terminology, images play various roles in numerous language games very different from each other, and in many of them the question of truth can have very limited relevance or be completely absent, as happens for example with decorative images. Despite the lamentations of those who know the principles of crystal formation, during the Christmas period there are abundant illustrations with impossible eight-pointed snowflakes: one can certainly hope for greater attention to these details, but we must also recognize that the "language game" of decorative images doesn't require any kind of commitment to truth, unlike scientific images of course.

A Case of True and False Images

Journalism is a particularly interesting area to analyze regarding image truth. Even images used decoratively (that is, not presented as evidence or testimony) that in other contexts wouldn't create any expectation of truth, in a scientific or journalistic publication must meet certain requirements.

In the World Press Photo regulations, among the most important photojournalism competitions in the world, the dual nature of image truth is evident. Truth as authenticity is important, and for example it's forbidden to combine multiple shots into a single image; however, the truly central aspect is propositional truth: it's therefore possible to crop photographs or adjust brightness and saturation as long as this doesn't hide information relevant to understanding the story that the photograph tells. It's even allowed to recreate an event, if this reconstruction is necessary to tell the truth and obviously if this staging is clearly indicated in the caption.

Another interesting episode to analyze concerns a sadly famous Time magazine cover: when in 1994 former athlete and actor O.J. Simpson was arrested for the murder of his ex-wife Nicole Brown Simpson, the magazine published Simpson's police mugshot on the cover. Time shrank the identification number—probably to balance the size with the title—and especially darkened the image, making O.J. Simpson's face blacker and more menacing. The operation became particularly evident because Newsweek used the same photograph, unmodified, on its cover, thus putting both versions of the mugshot before everyone's eyes. Time's choice to darken O.J. Simpson's photo was harshly criticized not only by civil rights groups, but also by journalists and the public, so much so that the magazine published a letter of apology worth a careful read.

The general approach is the unconvincing "we were misunderstood", but managing editor James R. Gaines raises some interesting points. First, he acknowledges that "altering news pictures is a risky practice" because the value of images in journalistic practice lies in their "documentary authority". However, he continues, we must recognize that no photograph is a neutral reproduction of reality, and if Matt Mahurin, the photographer and illustrator to whom Time had entrusted the cover, radically changed the image, he "lifted a common police mug shot to the level of art, with no sacrifice to truth". In short, Time's only fault would be not having clearly written that this was a photo-illustration—let's say not having clarified what the rules of the (linguistic) game were.

Because it's true that mugshots are often reworked for "secondary uses", generally souvenirs, for which truth is secondary. No one would have criticized—or at least not with the same arguments—if such an alteration had occurred for the image reproduced on some gadget; Time's cover is, however, another matter, another language game.

Generative AI and the End of Shared Codes

To summarize: our relationship with images is complex and multifaceted and unfolds—to continue using Wittgensteinian terminology—in a multiplicity of language games. In some games, including those in the journalistic fields, the truth of images has an important role that can essentially be articulated in two ways: on one hand, truth as authenticity (which concerns the image as an object, its genuineness and provenance) and propositional truth (which concerns the image as representation and expression of propositions).

So far we have avoided focusing on images produced by generative AI and this is for two reasons.

The first is to highlight how disinformation and misinformation weren't born with artificial intelligence. In fact, although it's possible to use generative AI to create or modify very realistic but false audiovisual content, most visual disinformation doesn't rely on these deepfakes but uses cheaper techniques, called cheapfakes, such as slowing down or speeding up existing videos or cutting part of the frame or footage. An interesting recap of visual disinformation tactics and impacts is this review from Newman and Schwarz.

Obviously, the development of generative AI, and the growing ease of use, will make deepfakes increasingly cheap, as well as increasingly difficult to identify, but it's important to recognize that the problem of image (and video) manipulation wasn't born with current technologies. We must also bear in mind that, however powerful, these technologies have limits. And it cannot be ruled out that part of the poor results, found in several studies, in recognizing images generated through AI tools is attributable to the truth-default effect, the cognitive state that according to Timothy R. Levine characterizes interpersonal communication and that leads us to assume, without conscious reflection, that what other people say is true. This mechanism, which according to Levine allows efficient communication and guarantees social cooperation despite making us susceptible to deception, could also concern images.

The second reason why we've focused so far on the "pre-AI" era is that to understand how (and if) artificial intelligence is changing something in our relationship with the truth of images, we must have an account of the previous situation. An account that, as we've seen, presents a certainly complex situation, with gray areas and difficult cases, but in which overall human beings move with a certain confidence, understanding and managing the shared codes that regulate the production and reception of images in different contexts.

We make mistakes, sometimes we lose the game but at least we have a fairly clear idea of what the rules of the game are.

Evolution or Revolution?

What happens now that generative AI allows us to produce and modify various types of images, from elaborate scientific illustrations to everyday photographs?

On one hand, we might think that generative AI will impose new codes for reading and interpreting images and, after an initial phase of disorientation, we'll become familiar with the new rules of the language games involving images. In a manner similar to what happened a few years ago with the advent of digital photography—which had fueled fears that proved unfounded—or, going further back in time, with the development of photography in the nineteenth century or with the Renaissance idea of the painting frame as a window from which to look at the world.

I'm aware of running the risk of ending up like the many authors of articles who, as mentioned, feared nefarious social consequences due to the spread of Photoshop, but I believe there are valid reasons to argue that generative AI won't merely impose new codes, but will essentially wipe the slate clean of existing ones, at least as far as image truth is concerned.

The problem essentially concerns the numerous indications we derive from the aesthetic and material characteristics of images. Think about image quality: a grainy or blurred photo is generally perceived as reliable testimony, especially for those situations like wars and natural disasters where it's difficult to have time to care for the photo's aesthetics. These are images that an AI has no particular difficulty producing, while paradoxically technical improvements in photographic equipment allow obtaining good quality images even in extreme conditions. We had an example with the photo of the July 2024 assassination attempt on Donald Trump, taken by Associated Press photographer Evan Vucci. The image, showing Trump with his fist raised and blood on his face while being protected by Secret Service agents, with the American flag waving in the background, was initially considered false precisely because of its composition "too perfect to be true". After all, there are several AI-generated images of Trump, some carelessly published even by news outlets, so skepticism is understandable.

It's not simply a matter of learning new codes for interpreting images related to technical improvements or social changes: here, simply, the characteristics of photos stop providing us useful indications about the truth, variously understood, of those images.

With particularly relevant consequences for those images—scientific, journalistic, documentary—for which the connection between authenticity and propositional truth has traditionally been stronger.

Fakes Without a Cause

With AI, it's generally easier to obtain a false image, in the sense of inauthentic, compared to a true one. This means that strong motivations—economic, political or ideological—aren't needed to commit to producing a convincing and realistic fake. Several images generated through an AI and mistaken, in some cases even by newspapers, for authentic ones weren't created to deceive or disinform, but as simple pastime.

This isn't a secondary aspect: the effort necessary to create a false image is often cited as an argument in support of the authenticity of photographs or other images used as evidence. The argument "who would ever bother to falsify this evidence" can in fact no longer be used.

According to Hume, the wise person proportions their belief to the evidence.

The spread of generative AI reduces, as we've seen, the reliability as evidence of images and photographs: the wise person is therefore called to proportionally reduce their belief, thus doubting all images—including true and authentic ones. This is a phenomenon known as the "liar's dividend" that allows people, particularly those politically active, to escape the consequences of accusations and scandals by taking advantage of this widespread (and, let's reiterate, reasonable) skepticism. In practice, faced with an embarrassing photo, it's enough for the politician in question to say "it's a fake" for at least part of public opinion to doubt the solidity of the accusation: making people believe that truth is unknowable is easier than supporting one's innocence.

It would be an unacceptable idealization of the past to think that before generative AI we weren't called to an exercise of critical thinking—to proportion belief to evidence, to use Hume's words again. The difference is that now this exercise of critical thinking must be based mainly on the credibility of whoever presents that image, since the image itself has stopped giving us indications. It's a practice that's based essentially, if not exclusively, on trust, a good distributed in a strongly unequal way in our polarized society. How much do we trust the current government, or a past one closer to (or more distant from) our political sensibility? How much trust do we place in independent bodies like the European Food Safety Authority or the European Medicines Agency? Are traditional media or “independent reporters” on social media more credible?

It would be, again, an unacceptable idealization of the past to say that, before the spread of generative AI, photographic images managed to bridge groups that diverge in evaluating the credibility of institutions. Just look at the criticisms made by moon landing conspiracy theorists of the photographs taken as part of the Apollo Project—not only before generative AI, but even before the advent of digital photography—to realize that images have always been an object of ideological and political confrontation as well. But precisely the discussions about the absence of stars in the lunar sky, the shape of shadows and the folds of the flag—to summarize the main conspiracy fantasies surrounding the lunar missions—show how photographs were at least common ground for discussion, something worth considering as a source of truth.

With generative AI, this role risks being lost and images risk transforming from bridges of mutual understanding into walls of incomprehension.

A Provisional Conclusion

As mentioned, with images we do the most diverse things. One of these things has to do with images' ability to communicate reliable information about reality (to "be true" in what here has been defined as "propositional truth"). It's an important function because images are—or were—generally considered "true until proven otherwise": whoever intends to exclude them from the premises of a public discourse must motivate this exclusion, bring reasons why the image isn't true (isn't authentic, doesn't tell the truth).

The spread of images produced through the use of generative AI makes it increasingly difficult to maintain this truth-default attitude. In other words, images can't do, or can't do as before, some of the things for which we used them. To return to Wittgenstein's metaphor of the toolbox, it's as if suddenly the wrench could no longer tighten bolts. We'd be rightly disoriented and it would take us a while to understand if we're doing something wrong, if we need a new wrench or a completely different tool.

Outside the metaphor: maybe we should simply get used to a world in which the truth of images depends solely on the (debatable) trust we have in whoever presents that image to us. Or maybe, as has happened in the past, for example with digital photography, we should simply develop new shared interpretative codes that, once acquired, will become the new normal (waiting for the next technological or social change). In the latter case, I hope this text will manage to make even a small contribution to developing a more conscious media literacy, respectful of the many truths that we human beings find, and put, in images.