Beauty and the Neuroscientist: A Conversation on Neuroaesthetics with Semir Zeki

Can a brain scan prove you're lying about beauty? Does hate have evolutionary advantages? In this interview, neurobiologist Semir Zeki—father of neuroaesthetics—challenges our assumptions about art, love, and what it means to experience something as beautiful.

I remember that, when I was a child, I had this big book about the human body. It was a fascinating read: I read how fresh air goes to the lungs and then there, in the alveoli with the surface of a football field—I don't know why they thought an early teenager would understand pulmonary and systemic circulation but not square meters—exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide with the blood, I read how the heart pumps blood, how white blood cells attack viruses and bacteria and sometimes they misfire producing allergies, where the salty or sweet receptors in my tongue were, and so on. By the end of each chapter, I could see that the things I feel—my breathing and heartbeat, the taste and cold of ice cream—come from tiny processes in cells and molecules.

It was obviously an illusion—but that's not the point. The point is that there was a notable exception, in this understanding. The chapter devoted to the brain explained how neurons transmit chemical and electrical signals and wow, it's amazing, but what does this have to do with my mind? I mean: I have to pee because my bladder is full of filtered blood because my body has to get rid of the waste of cells' operations, the passage from nephrons to the urge to find a restroom is crystal clear. But what is the link between some neurons that receive and send signals and the thought "I must find a restroom"?

I read that chapter several times and at first I thought it was my fault: like all other chapters, the answer was there but it was too difficult for me to understand. After maybe six or seven times I started to realize that I wasn't missing anything: there was no answer, in that book, on how the brain, a bunch of neurons, can think. It was a mystery, at least for me but I started to think that it was a mystery also for scientists.

Years later this suspicion was confirmed many times. Yes, I studied philosophy, so my approach to these topics is maybe biased, but I'm quite sure—I have no certainty here, as anyone else—that we can link certain mental phenomena to certain brain parts, but the properties of the two levels will remain different. You can try to grasp the idea with an analogy introduced by Spinoza: a curved surface is convex on one side and concave on the other; just as the same surface is both convex and concave depending on perspective, mental phenomena and brain activity might be two aspects of the same underlying reality.

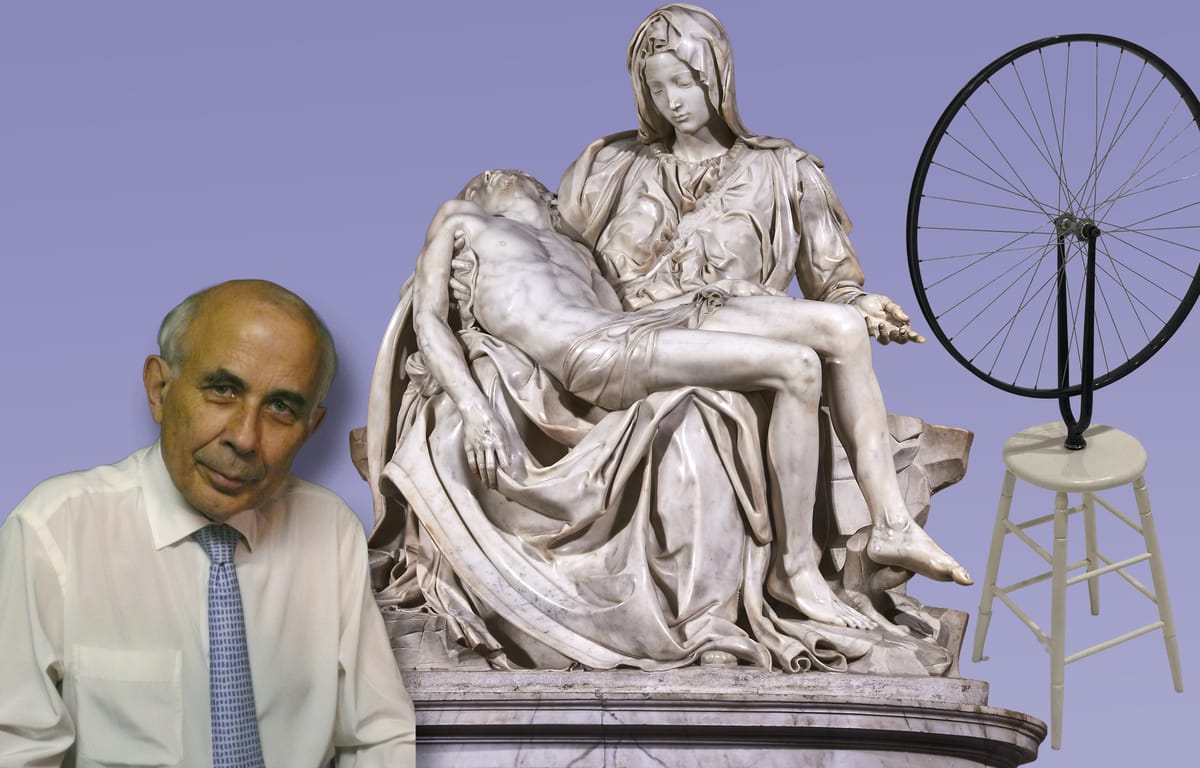

That's why, the first time I heard of "neuroaesthetics" I was curious but also a little suspicious: wow, a science that puts together neuroscience and the experience in front of an art piece—but in order to do what? To try to reduce our aesthetic experience to brain circuits, to find a neurological explanation of why Michelangelo was a greater artist than Pietro Torrigiani, following my childish dream of understanding the mind starting from neurons? Or to gain some insight of both the brain and the aesthetic experience? The answer to this question is nearer to the latter than to the first, as we can read in scientific articles and books written by Semir Zeki, the neurobiologist who started this field of research; I cite here the most famous: Splendours and Miseries of the Brain: Love, Creativity and the Quest for Human Happiness, published in 2009.

When, in 2024, Zeki was invited to Lugano for a public lecture about how art changes our brain—part of a course at the Università della Svizzera italiana in collaboration with IBSA foundation for scientific research—, I met him for a long interview.

Professor Zeki, I hope to have more challenging questions, but I start with a quite obvious one: what is neuroaesthetics?

It's a reasonable question. Neuroaesthetics is really a branch of neurobiology. It's a relatively new discipline which tries to answer the question of what are the neural mechanisms, the brain mechanisms that are engaged when we have aesthetic experiences and all that is allied to aesthetic experiences. Experience of love and desire and beauty – beauty from sorrow, beauty from joy, etcetera. Neuroaesthetics does so in the belief that these experiences, which are often considered to be subjective experiences, can be objectively studied and quantified. The other feature of neuroaesthetics is that it believes that all human activity, including activity in the arts and the sciences, is derived from the organization of the human brain. So you can get a lot of insight into brain organization by studying great novels or great works of art or even the law. They're all done by the human brain. And if you do that, you'll find that at a basic element, there are huge similarities across mankind. So it gives you a huge insight into the organization of the brain. And once you have studied, let us say, kinetic art as an example, you will get a very good idea of the brain mechanisms that are engaged in the perception of visual motion, and indeed the history of kinetic art shows that if you study it carefully, you would understand exactly how the brain does it.

There are many suggestions in your answer. To start: do you also include love in neuroaesthetics?

Yeah, sure. Because love is an experience that is supposedly subjective—I don't think it's that subjective. When you fall in love, very definite mechanisms in the brain are active, and studying the literature of love gives you huge insight into how the brain is organized: in fact, the concept of love is best derived now from studying the literature of love. Now, what many people will say is: what is a scientist doing reading literature of love? And my answer is that if a scientist is interested in a question, he should look at any source which gives you information about the question. And if he refuses to look at that source because it's not scientific, then he's a bad scientist. A good scientist will study any source.

I have the impression you are describing a two-sided heresy: on the scientific side, because you studied something particular like love, art, emotions; from the 'romantic' side, because it has to do with brain circuits.

Well, in fact the scientists, at least the very good scientists, have been extremely supportive. The difficulty has come really mainly from a few historians of art and a few philosophers. There are many historians of art who are very supportive, but historians of art study something very particular: they study the influence of one period on another. Neuroaesthetics is much more general: neuroaesthetics is trying to understand how all human brains are organized. So neuroaesthetics is not especially interested in the question of the influence of one period on another or the characteristics of, for example, the early Renaissance or the high Renaissance.

It's a very great leveler because it assumes that all humans, irrespective of their ethnicity, culture, gender, sexual orientation, etcetera, are capable of experiencing beauty and they're capable of experiencing love. Now, what they find as beautiful or as lovable is different, of course, but they're all experiencing it. So there is no difference between them at all at this level. And it also makes the very reasonable assumption that all humans, regardless of race, culture, etcetera, are capable of recognizing a human face. They know when a face is human, and they also are all capable of recognizing when a face is angry or sad or happy. There are no exceptions to this. So at a basic skeleton, neuroaesthetics makes quite valid assumptions.

Now, one reason why people make objections—let me repeat that the very good scientists and the very good art historians don't, but it's greater among art historians, and one or two philosophers—is to say "you have to take into account context, you've got to take into account cultural differences, you have to take into account differences in development of children". All this is true. But neuroaesthetics is really a medical subject. And in medicine, you see, you study the kidney, for example, in great detail. But once you study the kidney in great detail, it's true of all kidneys. Therefore, a kidney specialist, a nephrologist, does not have to make allowance for one particular person—he or she knows what the kidney is like and knows the departures from it. And the same way with the heart and the same way with the brain: you have to understand the basic organization before you study the departures. The departures being that yes, if somebody grows up in China instead of Italy, or in England instead of France, they will have differences, but these are superimposed—they both can do language.

So neuroaesthetics is not interested, and therefore cannot explain, why for example an artist uses a specific color?

No, neuroaesthetics does not go into questions like that. This is for art historians. But you see, even though neuroaesthetics does not go into these questions, neuroaesthetics is still heavily influenced by discussions in philosophies of art and in philosophies of aesthetics. I mean, one of the biggest questions asked in neuroaesthetics is actually derived from an art historian, which is Clive Bell. Clive Bell in England in 1914 asked a very powerful question. He said: what is common to everything that arouses aesthetic emotion? Now you can convert that into an experiment—you can show people works of art derived from different sources and see what is common to all of them.

So we can study literature, art, and also love to understand the brain. And maybe we can study the brain to understand some very general aspects of art.

Well, not quite, because neuroaesthetics is a scientific discipline devoted not to study art. It's devoted to study the brain. But it can understand something about the brain by looking at works of art because these are produced by the brain.

Neuroaesthetics looks at the product, art, to understand the cause, the brain. But isn't this very different from, say, chemistry—where analyzing a reaction's products directly reveals the process that created them?

Yes. But above all, the study of art raises questions—the important thing is the question that it raises, and if you can convert these questions into experimental questions. For example, if you take the Cubists. Now the aim of the Cubists was to see how an object maintains its identity when you view it in different conditions: different distances, different lighting conditions, different context. This is a problem of form constancy. Now this is a problem that neurobiologists are studying now, but it's a question that was addressed by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque in 1905.

What kind of experiments do you do in neuroaesthetics?

We do two or three kinds of experiments. One is imaging experiments. So you ask people to look at beautiful things and you see the activity in their brain and where it's located and whether it's quantifiable.

We do psychophysical experiments. For example, one quick way of stopping any discussion on beauty is to say it's subjective. But that's not true. You can take 1,000 people and show them very beautiful faces from Japan, from Africa, from Italy, from France, etcetera, and you will find there's very great consistency. So to an outside observer, this is not subjective–it's very objective.

The third method is the method I told you about–the method of looking at works of art or listening to bits of music and seeing what you can extract from them. Now there is another method which is supremely important and which we have done, which is looking at the beauty of mathematics. Because Paul Dirac, Albert Einstein, Bertrand Russell, and many others and above all Plato, thought that the highest form of beauty is the beauty of mathematics because it gives you an idea of the structure of the universe. And a lot of the findings in physics today were apprehended through the beauty of the mathematical formulation before they were experimented on. I mean, can you believe it that the theory of relativity is still being experimented on? But Paul Dirac said that the mathematical formulations were so beautiful that beauty must take precedence over simplicity in mathematical formulations.

I'm not sure if it's relevant for neuroaesthetics, but do you think that the sensibility for beauty is a useful trait and was perhaps selected by evolution?

Yes, well, I mean it must have been selected for—certainly some aspects are true. What's not quite true is that mate selection is not really done on beauty, it's done on fitness. So you find that women don't look for very handsome men who are very thin, etcetera. They look for men with rosy cheeks who look as though they are good providers or can be good providers, and men look for women who are rounded enough, who look as though they could be good mothers. So this is not based on beauty, but there is of course an element of beauty in choice. And six-month-old children tend to look more towards beautiful faces or beautiful bodies, same as adults. So these are almost inherited qualities. Now, people think it's the golden ratio. It's not the golden ratio: there are various aspects, you've got to have the proportions, you've got to have the relationship, all this has got to be right. But that in itself is not sufficient. There is another ineffable quality, and I don't know what it is, but neuroaesthetics would be the subject to address that question.

Ludwig Wittgenstein spoke about linguistic traps: we speak about the beauty of a human face, the beauty of a person, the beauty of a piece of art, the beauty of mathematics. We use the same word "beauty", but is that also the same concept? Because I think a beautiful woman or a beautiful man is very different from a beautiful equation or beautiful mathematical demonstration.

Correct. But a beautiful woman or a beautiful man or a beautiful landscape or a beautiful car – they all have got two qualities: they give pleasure and they are rewarding. And there's a third quality, which is that they are often desirable. I mean, when you look at a beautiful house, you may think: I would love to have this house. Or a beautiful painting: I'd love to have this painting. Or a beautiful woman or whatever it is. Now it so happens that the activity in the brain that occurs when you experience beauty is in the same part of the brain as that of reward and pleasure.

Philosophies of aesthetics have tried for 2,500 years to define beauty and they don't have a definition, but we've got one—but in the context of brain activity only.

And this definition is…?

The definition of beauty is that whenever you experience beauty, regardless of its source, whether it's mathematical or moral or visual or auditory or pleasurable or sorrowful etcetera—it always correlates with activity in a specific part of the brain, the medial orbitofrontal cortex. Now other parts of the brain might be active too, but this part of the brain is always active. So in a sense, if you look at pictures and you tell me they are not beautiful for some reason you have in mind, and I find activity in your medial orbitofrontal cortex, I'll say you're lying. And also, if you say they are beautiful and I don't find activity in the medial orbitofrontal cortex, I'll say you're lying. So there's something quite objective about it, which brings me to the point that beauty is an abstract thing, because any source that gives you pleasure and is rewarding to you and which you desire is correlated with activity in the medial orbitofrontal cortex.

We speak about all human brains, for mankind, among many traditions and cultures in the world. This brings me to the topic of neurodiversity and neurodivergence, for example, people with some form of autism. In those cases, does their brain also work for the perception of beauty and art?

Well, I mean, this does not negate the point I was making. You see, what is interesting in studying things like autism and even Alzheimer's disease is that we concentrate on what people lose, what people are not able to do, but we never concentrate on what they are able to do. And they are able to do quite a lot. Even Alzheimer's people, even at relatively advanced stages of Alzheimer's, can still talk—it's a terrible disease, I'm not minimizing it. And autism, of course, is a big spectrum, and there are lots of things they can do. The only time when people lose the capacity to experience beauty is a syndrome called anhedonia. It's not very well studied at the moment because it's a relatively new subject. I mean, addressing the question specifically of what happens in the brain, what have you lost in the brain when you are not able to experience beauty anymore or pleasure.

You said neuroaesthetics brings something to aesthetic experience which was believed to be subjective and said we can in some way quantify it and make it objective. So is it possible that neuroaesthetics can answer arguments like, for example, is Mozart better than another composer? Can neuroaesthetics make some sort of quantification of the beauty?

No, at the moment it cannot, but I don't know what will happen in the future. I mean, is Mozart better? It's a very difficult thing: some people think he's better, but why they do, we don't know, and neuroscience has not addressed this question yet. I mean, neuroaesthetics started in 1995, it's very new. At the beginning, the first 10 years, of course many people were reluctant, but now there are courses in neuroaesthetics at Harvard, at Duke University, at Stanford. So it's become quite a wide field now. But these differences cannot be addressed yet.

But you don't think that in the future we can have answers to those questions? A recurring question in Italian literature is who was the best poet between Dante and Petrarch, but neuroaesthetics cannot address this question.

Well, no, I think it can be addressed. I mean, look, we can address it now, but in a different way from what you mentioned. We can get 200 Italians and give them poetry of Dante and poetry of Petrarch to decide between the two. I suspect that you will find – I'm not Italian, so I'm not sure – I suspect that people would prefer Dante. Petrarch is more opaque.

I agree.

Yes. Now this is the first step, but then you can imagine going further and finding why Dante is preferred by most people. So although it's not been done at present, it can be done in the future, it will be done. Basically, what one has to understand—and I think people find this very difficult to understand, though I don't know why— is that neuroaesthetics is a very core subject because it addresses all active human behavior. Now, the question of moral beauty is a question that neuroaesthetics has addressed. But then that also takes you further into understanding, into asking a question of: does the law have a moralizing duty or moralizing effect, or is it a protection against immorality?

Another thing that neuroaesthetics has studied is beauty versus ugliness, and love versus hate. Now hate is condemned often by everyone as an evil, wicked thing to do, but actually hate is part of the organization of the brain. People must hate, and hate has got advantages in the sense that you can bond with other people, fight other people and gain more land or more property whatever it is. So you dominate another group, and when you dominate another group, that's got an evolutionary advantage. So hate – I don't know if anyone has recognized this – is a very important biological factor. But hate, in terms of neurobiology, is neutral. Hate is something that you possess, it's part of the neural apparatus.

It's neutral from a neurobiological perspective?

From a neurobiological perspective, yes.

But I think that from a moral point of view we can say that it's better to love than to hate.

Oh, we can say that it's better to love than to hate. But we cannot say that hate is a wicked thing because hate is part of us. It is like saying that preferring meat to vegetarian food is wicked. It's not wicked. Or, to get a better example, preferring cucumbers to carrots – it's not wicked, it just happens to be part of us. There is a French author by the name of Céline who is ranked very highly amongst the French. He's a cynical, very big antisemite, actually – a very cynical author who is regarded as a great author in France and who believed that man hates because he has to hate.

But in the case of love and hate, we have two different levels of evaluation. One is the neurobiological, evolutionary level, and maybe from another level is the moral reflection.

Yes, but love and hate have things which are in common. There's a biological imperative behind both. When you love somebody, it is no good my telling you: what are you crazy? You love this person? Look, she's of the wrong class, she's of the wrong nationality. It doesn't work. And with hate, if you say: why do you hate this person? Why do you try to harm him? It doesn't work either. If you hate freely, you do something about hating them. Now they also have got the common thing of advantages. If you hate somebody and you are capable of destroying them, there will be advantages to you – certainly psychological advantages. If you love somebody and you want to be with them, there are also advantages to you.

The question of why we say that love is good and hate is bad is also a question that's interesting to study from the point of neuroaesthetics. Why do we say that? I mean, well, sometimes we object to it and sometimes we do not. Let me give you the example of Myanmar, Burma. In Burma, suddenly Aung San Suu Kyi, who was the effective ruler of Burma for many years and got the Nobel Prize, decided that the Muslim Rohingyas were no good. Now these people are ethnically identical to the Burmese. What were the advantages? And why is it that the people of Burma regard it as okay for getting rid of these people and the people outside regarded it as not okay? The rest of the world did not do much about it, but most people think it is not a good thing to do.

I'm among them. Changing subject, do you think that for an artist it is useful to have some basic knowledge of neuroaesthetics?

No, they don't need basic knowledge. What an artist has got to have is a brain.

Yeah, of course.

But apart from that, they need to know nothing. I mean, if Beethoven were living today and knew a lot about the brain, I don't think his music is going to improve. Now, some people are using neuroaesthetics or neurology, really neurophysiology, to compose according to what they think is artistic. I don't think it's very successful. On the other hand, it must be said that some of the great artists were very interested in the brain. Cézanne and Francis Bacon were very interested, but not to improve their art: they were just curious people intellectually.

So neuroaesthetics is just a scientific effort?

It's basically a scientific effort that believes that it can make insights and inroads into huge sections of human behavior and conduct to understand the brain.

You spoke very often of human behavior, but is the aesthetic experience a behavior or is something that happens in my mind?

Experience is not a behavior, it's an experience. But, what is really important to understand is that this is an experience that is very much dependent upon the brain. I think a lot of people today, in fact the majority, would think that beauty resides in the object, but in fact beauty resides in what the brain does to the object. And there are various new methods, which are a bit complicated to explain right now, which show that there are special interactions of the brain when you experience beauty. So it is entirely a brain operation. The point is, the brain operations are the same in different people of different ethnic groups and cultures.

So what is a beautiful object, a beautiful piece of art, can change because we have some individual differences and different cultural backgrounds, but the brain experience remains the same?

Yes, for things which you find beautiful. But, when you say the Italian Renaissance period was different from the Italian today, that's not true: they are the same. And which is why Dante is still appealing, and so is Michelangelo. So they are the same.

But the art produced today is different from the art produced in the past. We spoke earlier about Cubism: when Les Demoiselles was first exhibited, people were shocked—presumably they didn't find it beautiful in the conventional sense. Would a brain scan have shown different activity than we'd see today?

Well, Les Demoiselles is not the best example to take, because it has a very important position in the history of art. It was the precursor of the idea that an object maintains identity when you go around it and you look at it. The woman on the right – you don't know whether you're looking from the front or the back. And then Picasso and Braque developed this quite a lot. So the other reason why it's a very special painting is that it was really the first time it was acknowledged that this was a scientific experiment. Braque said it's a question: how does this object maintain its constancy? Now, there's another work of art which is even more important from the point of the history of art, which is the bicycle wheel of Marcel Duchamp. Marcel Duchamp said—and he's a revolutionary master—that it's art without an artist. All I need to do is take a ready-made object, sign my name, put it in an art gallery, and it becomes art. And this is the first time that he—and it's very important biologically—divorced beauty from art. Not all art activates the medial orbitofrontal cortex. Not all art is experienced as beautiful. Much of it is not experienced as beautiful. And so these are paintings that are iconic because they are iconic in the intellectual history of art. You see, before the time of Marcel Duchamp, it was, and still is in many quarters, believed that the function of art is to produce beauty. But this is not true.

So in this case, maybe the ready-made from Marcel Duchamp – it's pleasure but not rewarding, perhaps?

It is not rewarding, it's not pleasurable, and it's not beautiful. It is just questioning what the function of art is. It's an intellectual exercise. That's all it is. I mean, beauty is not in the object but in the philosophical reflection that this art represents. It's a sort of mathematical beauty, theoretical beauty.

Mathematical beauty?

Yes. Mathematical beauty is very satisfying. Mathematical beauty has a special status. When you experience mathematical beauty, you do get a real pleasure of beauty, and you say: this is right, this is correct. Now when the Futurists exhibited their work in Rome, the critics at that time said: only this is the truth, the rest are all paintings. So mathematical beauty points toward the truth. For example, black holes, the expanding universe, dark matter, dark energy—these are all conclusions arrived at by mathematical beauty, and then the experiments showed them to be true. So you know, in a sense, "truth is beauty, beauty is truth", as John Keats wrote, is true.

There is also a moral beauty?

These are not my experiments, by the way. Moral beauty has been studied in America and in Japan. Moral beauty is when you ask people questions such as: you are very hungry and there's a big piece of steak which you can have, but you also have the option of not eating it and giving it to a hungry child. The first one is satisfying yourself. The second one is a much higher moral ground. And you know, for many people, killing is wrong even if somebody has done something. Now one way is to kill somebody in revenge; the other way is to say: well, even though they have done wrong, I will not kill them. That's a moral high ground. And things like that—you know, if you're very cold and you see a very shivering child, you give up your coat. When people are asked these questions and they give these answers, you find activity in the medial orbitofrontal cortex.

Last question. You are considered the father of neuroaesthetics. What was the feeling when you started?

Well, the feeling was very simple, actually, and I can tell you exactly how it started. I got a letter from a young man in Japan whom I had never met. He wrote me a letter saying: "Professor, I am Japanese. I know nothing about Christian culture. I know nothing about the Virgin Mary. I never knew Jesus Christ. But when I went to St. Peter's Basilica in Rome and saw the Pietà of Michelangelo, I came out in tears. Can you explain that to me?" You see, I thought to myself: I've spent 20 years studying the brain and vision, and I cannot answer this question. So I'm going to start studying. This is a very serious question.